Disruption Claims – The Art of the Possible

We read from time to time articles and learned papers about the correct way to establish quantum values for claims for disruption on construction projects, or loss of productivity as we prefer to call it.

Construction works includes anything from excavation through to final painting on building works and including the entire spectrum of civil, marine and process engineering processes.

In simple terms, loss of productivity means that the contractor incurs costs executing the construction work over and above what they would have expected because of some form of disturbance, hindrance or interruption.

Loss of productivity affects a contractor’s “direct resources and costs” i.e. productive labour, equipment. In simple terms, the contractor incurs additional labour and / or equipment hours and higher costs resulting from inefficient working. Potentially it might also face claims from subcontractors who may also be affected.

If it is caused by reasons attributable to an employer, that may result in a claim for additional payment. The extreme example is “idle time” when men and machines are not working and therefore not earning money for the contractor, but still costing money.

Loss of productivity, however, can cause critical delay that will affect a contractor’s “indirect resources and costs”, i.e. on and off-site overheads (refer to Appendix 1 below for details).

In summary, the contractor is not working as efficiently as it could have done, absent the disrupting event(s), and those events have therefore cost the contractor more money with no benefit.

The authors of this article have all worked for, or within construction companies and consultant organisations on live projects as well as on post-contract disputes. We are well aware that the contractors’ records that are needed to establish entitlement to additional payment on loss of productivity claims (and others) can range from good, down to virtually non-existent.

Based on our individual and collective knowledge, we start off every assignment on a problem or loss-making project with a slightly different attitude than the learned papers would have us do. We start with an examination of the information available and determine what we describe as “the art of the possible”.

This article focuses on money, as all disputes are ultimately about money; the contractor wants more but the employer does not want to pay. The rest is a variation on a single theme.

We know the types of documents and the usual sources of information that ideally, we would like to examine. The first task is to establish what is actually available. That will determine what is possible and how the claims may be structured or checked and to assist in establishing quantum values and possible entitlement.

The preliminary research in establishing possible quantum values is therefore to understand what information there is.

Our initial “hit list”:

- Contract documentation including pre-contract correspondence;

- The tender prices;

- The contractor’s estimate;

- Submitted tender information such as labour histograms; resource allocated programmes or resource schedules;

- The contractor’s pre-contract enquiries to potential subcontractors and suppliers;

- Quotations received from subcontractors and suppliers (checked to determine if they were used in the estimate);

- The finalised subcontracts and supply contracts;

- The contractor’s costing systems and cost records;

- The contractor’s general correspondence to and from subcontractors and suppliers including any claims for additional payment;

- Details of the contractor’s complaints and the employer’s and / or consultant’s responses;

- Details of programmes and progress;

- Daily site reports and records of resources deployed on site;

- Labour timesheets and equipment records including hire charges; and

- Details of resources relating to variation work and or other claims that ought to be excluded when assessing loss of productivity values.

No matter how laudable the intent of textbook advice on claims or learned papers on the subject, there is a need to understand what pre and post-contract information is available, and what the contractor’s analyst and / or an appointed expert can do with it, as opposed to the text book theory as to what the contractor ought to have and do.

We do not proffer a counsel of perfection, because we seldom if ever find it, nor in many instances anything like it.

During one arbitration, one expert was taken to task as within his report he had included his instructions to his colleagues to determine the quantum of claims “beyond reasonable doubt”. It was pointed out by counsel that that term was a legal standard of proof required to validate a criminal conviction.

It is our understanding that the legal principle is the balance of probabilities that we understand to be 51% or more. If we are wrong on that point, then we are sure that we will be corrected.

What we look for is information that might establish the possible extent of the contractor’s entitlement to more money, obviously dependent on further analysis and the establishment of the employer’s liability.

We frequently find it helps in assessing cause and effect, to start looking in reverse order, i.e. look at possible effects in terms of losses and / or additional expenditure and then start looking for possible causes. In short, we “Follow the Money” (see also Construction Law Journal Article Volume 31 Number 8).

Our preferred preliminary action is to analyse where, when, and how much money the contractor either lost or simply experienced a reduced or zero profit. For example, on a US$ 100 million project scheduled to make 5% profit, zero profit or even a US$ 4 million profit, represents a loss to the contractor.

That process of identifying losses we then use to focus our investigations.

However, it is not good enough to simply demonstrate that losses exist, one must identify the losses and then link them to causes and establish the potential amounts.

Whether we are employed by the contractor or the employer, the research is identical. In the latter instance, if we are engaged by the employer, access to some documents including the contractor’s estimate can be problematic and can frequently be subject to an application for disclosure.

We understand any contractor’s concerns about disclosing its estimate as all of the authors of this article have worked for contractors and know that even within a contractor’s organisation, access to some elements of the estimate, particularly overheads and profit allowances are restricted. Our normal procedure is to examine the estimate in the contractor’s offices and only use such information as is necessary including, for example, allowances for overheads and profit. We are sometimes asked to sign confidentiality agreements which require that any details from the estimate are only for the purposes of arbitration or other purpose that we are engaged on and have no concerns about doing so.

The First Steps

1. What were the tender prices (if known)

If the information is available, we try to establish what the prices from the other tenderers were. That might provide an insight that a contractor’s estimate was accurate or, if very substantially lower than all the other tenderers, an indication that its estimate was low.

If the contract prices are reasonably close to some of the other tenderers, then the indications are that the estimate was reasonable. That is a good starting point.

If substantially different, then that might indicate some adjustments may need to be considered in assessing the contractor’s entitlement.

2. Examine the detail of the contractor’s estimate

That will establish how the contractor estimated the project; what subcontractor and supplier quotations it was relying on; and what allowances it made for overheads, direct and indirect.

The structure of contractors’ estimates are broadly similar, a typical example is shown below.

1. Direct Costs

a. Labour;

b. Materials;

c. Equipment;

d. Subcontractors.

2. Indirect Costs

a. Supervisory and administrative staff;

b. On and off-site facilities including temporary and common facilities and facilities for the Employer’s supervisory staff;

c. Indirect labour;

d. Indirect equipment e.g. general site transport, tower cranes and the like.

3. Overheads

a. Head Office overheads;

b. Insurances;

c. Bonds, financing, etc;

d. Fees – design, engineering, consultants, legal.

4. Profit

a. Speaks for itself.

A brief explanation of the typical estimate breakdown is provided at Appendix 1 to this document.

Summary

In summary, as noted above the elements of a contractor’s costs that will potentially be affected by disrupting events are related to the physical effort of construction (i.e. its direct cost labour and equipment, including the direct labour and equipment of its subcontractors), it is essential that these costs are analysed to determine the extent of the losses incurred (If any).

Increases, decreases, or changes to the work scope will affect a contractor’s direct costs, but these are normally compensated by other mechanisms within the contract.

Interruptions to regular progress to any part of the work scope can cause loss of productivity and additional cost to the contractor. Such interruptions may or may not delay overall progress of the project.

Critical delays to the project or elements of it will affect the contractor’s indirect costs but may or may not necessarily affect its direct costs; or at least not in any way proportionate to the actual delay. If a major problem occurs or contractors can see that a problem is about to manifest itself, in the normal course of events it will seek to minimise its costs, for example putting equipment off hire; transferring direct labour to other sites (always assuming that they can); and delaying starting times of other subcontractors. One cannot assume that there is direct relationship between “delay and disruption”. It simply is wrong. See the article “Delay and Disruption a separable duo” (Construction Law Journal, Volume 28 Number 7).

To assume that critical delay will affect the contractor’s direct costs is, in our collective experience, an assumption too far. It is not uncommon to experience critical delay without loss of productivity and it is not uncommon to experience a loss of productivity without critical delay.

On large sites, for example, there may be several “work-flows” involving geographically distant structures each working independently of the others and with different planned completion dates, but one contractual completion date. There may be a disrupting event to one of the individual work-flows caused by a temporary stop order pending a decision on, say, piping layouts. That work-flow may always have been scheduled to complete earlier than the others and did in fact do so, but later than it was planned. The effect of the temporary stop order might have increased the direct labour and equipment costs but was not in any way critical to completion of the project. Conversely, if the different work-flow or section of the project had their own allocated supervisory staff and / or equipment and / or indirect labour, then there may well be a claim for prolongation costs related to that section even though that section was completed earlier than the overall completion date. All depends on the detail.

The Second Steps

Having assembled the raw material available to the analysts and establishing a clear idea of information availability and a broad idea as to what is possible, the second steps can begin.

Much depends upon the contractor’s costing records and systems and, if applicable, that of its subcontractors and the analyst’s ability to inspect them.

The object of the exercise is to link possible losses or increased costs to the complaints. The better the contractor’s costing systems, the more likely it is that links can be established between the complaints and the costs.

However, the mere fact that a contractor has lost money in a particular period and / or in a particular operation or series of operations is in itself proof of nothing. It does, however, give pointers for further investigations. Comparing estimated and actual costs in as much detail as possible is the next step to establishing potential values of entitlement.

This process can also apply to prolongation and / or acceleration claims, but this article is focused on loss of productivity claims.

Loss of Productivity Claims

The preparation of loss of productivity claims are more difficult than prolongation claims which possibly explains why they are often not well structured and simply linked to issues of delay (the “delay and disruption” inseparable duo which, as noted above and in the article “Delay and Disruption a separable duo”, are possible to separate and indeed must be).

The reality is that delay and loss of productivity are quite different; rely upon totally different records; and need to be evaluated in a quite different manner.

They rely upon the contractor’s ability to:

a) Demonstrate its direct costs of labour and equipment normally over periods of time, say in days, weeks or months.

b) Demonstrate actual production in total terms over the same periods of output, e.g. square metres of brickwork; cubic metres of excavation, fill or concrete, or whatever the affected work disciplines are. On complex process industry projects, it may well be that the comparisons are more difficult, but the answer is to look for plausible comparisons.

c) Link actual progress of the particular activities or groups of activities and link that progress directly to labour and equipment hours (and ultimately cost) in the same periods of output.

d) The ultimate objective is to demonstrate that:

(i) the contractor was capable of achieving certain levels of productivity; the first step in the so-called “measured mile analysis”;

(ii) that there was an intervening reason during discrete periods where it was unable to achieve its normal productivity rates or outputs;

(iii) that the cause of the problem and therefore the underlying reason for productivity losses and increased costs were reasonably attributable to an event or issue that provides the contractor with entitlement to additional payment (the 51% issue referred to above);

(iv) there is a clear and checkable link to the additional costs or losses.

To be clear, it is possible that delays (critical or otherwise) can and sometimes do contribute to losses of productivity and that it is frequently the case that losses of productivity can cause or add to critical delay.

Determination of Actual Production

- Establish actual production by examining the detail of interim applications for payment and / or daily / weekly / monthly progress reports, supervisors’ reports, etc;

- Establish the costs of direct labour and direct equipment in as much detail as possible;

- Dependent upon the contractor’s costing records, that may or may not be relatively simple;

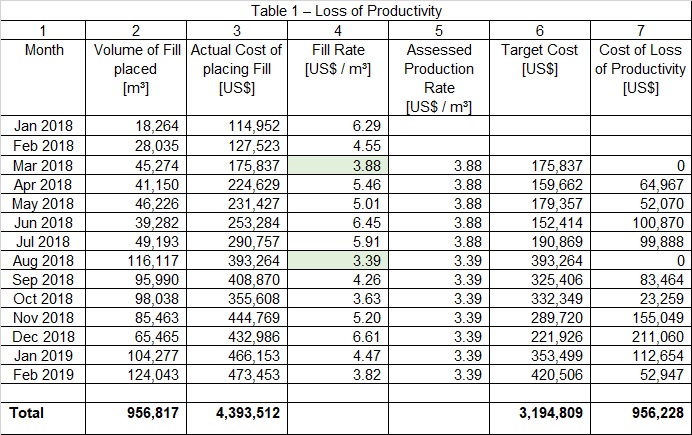

- Link actual production and costs (see Table 1 below);

- Establish achievable production norms, i.e. best performance;

- Identify losses where the contractor was unable to achieve optimum efficiency; and

- Look for causes of loss coincident in time with those losses.

Table 1 below provides a simple example of a project with a large volume of filling.

From the table, the following may be discerned.

In March 2018 the contractor achieved an actual “fill rate” of US$ 3.88 per m³ (column 4), calculated as the actual costs (column 3) divided by the volume of fill placed (column 2).

The assessed “possible production rate” (column 5) therefore was established as being equal to the value in column 4.

In looking for the causes of the contractor’s inability to achieve its previous performance e.g. March 2018, it is interesting to note the following.

In April 2018 the volume of fill decreased by some 10% but the fill rate per m³ increased by some 40%.

By May 2018 the fill volume was marginally higher (+/-2%) than in March 2018, but the fill rate per m³ was almost 30% higher.

In June 2018, the fill volume decreased over the previous month and the fill rate per m³ increased by some 28%.

In August 2018 the fill volume increased dramatically and the fill rate per m³ improved to US$ 3.39, setting a new efficiency rate for further investigation.

From September 2018 to February 2019 the volume of fill fluctuated substantially, all of the months had greater volumes than March 2018, the first “measured mile” but none of the months achieved the lower rate in March 2018.

The “possible production rate”, assumes for the purposes of further investigation only, that the achieved production rate in column 4 was optimal and represents a suitable “measured mile” of the outputs that should have been achievable subsequently had further events not occurred. The “possible production rate” might be equal to, more or even less than the estimate values.

In this instance the actual production rates are assessed from equipment and labour records.

Examining the results above, from April to July 2018 its production rate or efficiency decreased. i.e. its costs per m³ increased.

From September (2018) onwards production then declined over the following 6 months.

It is important to note that the losses in themselves do not provide an entitlement to the contractor.

That assessment provided information to the analyst to examine the circumstances within those months and find out if there was a discernible cause for the decline in production and increase in costs.

In the instances detailed above, there were demonstrable links to causes attributable to events outside of the contractor’s control.

At that point and only at that point does a possible claim for loss of productivity exist. The analyst has established “effect” (i.e. losses) and linked it subsequently back to causes.

Summing up, our advice on loss of productivity analyses is, start with the effect and look for the causes. It advises and provides guidance to the analyst where to look, and at what.

It may be observed that the first part of the analysis may produce some potential values, but the next steps are to establish a link between the “effect” and the possible “causes”.

There are in any analysis such as these many variables and it would be very rare that one could demonstrate with absolute certainty the links between cause and effect. In all our collective years of experience on projects on six continents, none of us can recall a “beyond reasonable doubt“ scenario, but we are aware and have experience of situations where productivity losses were capable of being established with a probability rate of 51% or greater.

Summary Conclusions

Start with assembling the necessary documents and information.

Examine the contractor’s costing information and base your strategy on what is available (having firstly satisfied yourself that there are no more documents available).

Do not conflate or confuse delay and loss of productivity. They are quite different as Appendix 1 below illustrates, and they need entirely different methods of assessment.

As noted above, the end is where we often begin, exploring the art of the possible.

Postscript

In a recent arbitration a delay analyst remarked that there could not have been disruption at a particular point in the contract because there was no delay.

Perhaps he was led to that view by the SCL Protocol 2nd edition, February 2017, Guidance Part A, paragraph 1 (Page 9) that states:

“The construction industry often associates or conflates delay and disruption. While they are both effects of events, the impacts on the works are different, the events may be governed by separate provisions of the contract and governing law, they may require different types of substantiation and they will lead to different remedies. Having said that, the monetary consequences of delay and disruption may overlap and, further, delay can lead to disruption and, vice versa, disruption can lead to delay” (emphasis added).

We agree with the paragraph quoted above, particularly the parts emphasised.

However we do not agree that “they may require different types of substantiation“. They undoubtedly require different types of substantiation.

As noted above, loss of productivity affects a contractor’s direct resources and costs i.e. productive labour, equipment. In simple terms, the contractor incurs additional labour and / or equipment hours and higher costs resulting from inefficient working.

Paragraph 7 of Guidance Part A (page 10) states:

“Delay and disruption are inherently interrelated… .”

We cannot explain why there is this confusion between a statement that says “…the impacts on the works are different … they may require different types of substantiation and they will lead to different remedies“

and

“Delay and disruption are inherently interrelated…” (emphases added).

Anyone who has worked on sites for any length of time knows that if there is a delay to a part of the work that cannot be executed, contractors will not simply stop labour and equipment from working (assuming that both are involved) but if possible will redeploy men and machines to other parts of the project, or even move them to other projects. The same will apply to subcontractors.

In our collective experience working for contractors, there are very rare examples of projects where delay and disruption were inherently interrelated. One project, however, springs to mind.

The project involved a 14-metre-deep excavation over an area in size much larger than a football pitch. An approximately 3 metre diameter chasm appeared in the ground in front of a D9 bulldozer that almost dropped into it. The Engineer correctly issued a stop order on safety grounds. A cavity probing operation was set up using a specialised company that took several weeks. Eventually, after a remedial works operation, the project was restarted.

In the meantime, much of the heavy equipment was put off-hire and some (but not all) of the contractor’s owned equipment and operators were moved to other projects. The delay period was fully compensable, but the loss of productivity claim was relatively limited.

The above example where a project-wide “stop order” was placed is an example where the cause of the increased costs were inherently related, but the actual costs were simply quite different in terms of supporting facts and extent.

Loss of Productivity in the Post Lockdown World

There is no question that the Covid-19 epidemic has caused mayhem to many industries including the construction industry. See our article on the subject “The Real and Present Danger Facing the Construction Industry”.

The consequences in terms of losses including productivity losses are and will continue to be substantial. We recommended in the article that employers and contractors engage and seek agreements if possible and subject to any contractors’ legal entitlement we also recommended that contractors:

“talk directly to the Employer and Consultants and seek a consensus on ways of mitigating the effects both potential and real. It would also assist all parties in trying to move things forward in a measured way.

Even if you achieve a broad measure of project cooperation, we still recommend that you undertake some measures now to record events.

These include:

-

-

- Ensure your daily resource levels are recorded;

- If works are proceeding, record the resources employed on the various activities;

- If works are idle (temporarily or permanently) record the resources that are affected;

- Record the progress, if any, that is achieved;

- If you are able take photographs of what is (or is not) happening;

- Check your material delivery schedules;

- Contact your suppliers for updates on projected deliveries;

- Check the impact of those delivery updates on your programmes;

- Contact your suppliers and subcontractors and maintain regular dialogue as to labour,

material, plant and equipment availability. Record the discussions in writing; - Ensure the records are accurate;

- Keep your Employer up to date with the potential impact of all of the above on your ability to proceed and progress the construction work and ultimately complete the Project. Record such discussions in writing;

- Issue notices and or early warnings as required under the Contract to protect your position;

- Set up database of the above records so that it is readily available;

- Ensure all emails are logged and available in a central file;

- Establish a secure back up file for all the records / documentation; and

- Keep all records until any discussions / issues have been fully and finally resolved.”

-

Finally, on the subject of Covid-19, some Governments including the United Kingdom have provided some forms of financial relief to industry including the construction industry. Analyst’s should not forget that there may well be some form of income to be taken into account in the final summation.

This article was based upon the collective experience of and contributed to by: –

Mike Bradley

Joe McAloon

Alan McEwan

Tony Walsh

Kevin Wishart

Iain Wishart

Appendix 1

1. Direct Resources and Costs

As a general rule these include the following.

Direct labour, materials, direct cost equipment and subcontractors are related to the physical volumes of work to be constructed and the anticipated timing of various elements of it. Different disciplines or trades will not only start and finish at various points along the construction calendar, but the labour gangs will vary in size at diverse times as the workload increases or decreases. The same applies to equipment and equipment usage.

Tendering contractors will rely in varying degrees on quotations from subcontractors. The subcontractors’ costs are the prices submitted by subcontractors to the main contractor and will include the subcontractors’ direct and indirect costs including the individual subcontractor’s own overheads and profit.

Material costs as a general rule are not affected by loss of productivity, but as with all general rules, there may be exceptions that require to be investigated and quantified.

2. Indirect Resources and Costs

The “indirect costs” as a general principle are not related directly to the physical volumes of work to be constructed, but to the time that the contractor expects the various elements of the project to take and the various indirect resources that it will utilise. Having said that, obviously larger projects, as a general rule will take longer than smaller ones. Indirect costs include the following.

Supervisory and Administrative Staff

Estimated on the basis of the expected time required on the project, normally in weeks or months. Note, however, that estimators do not assume that all staff will be on site for the contract duration, but core staff will start on or shortly after project commencement, other key staff will arrive at various points during the construction period and demobilisation of staff will commence at various points, some surprisingly early in the construction process.

Site Facilities

The costs of project offices, warehouses, temporary structures, and the like. On remote sites it might include the costs of concrete batch plants, rebar yards and precast yards. The estimate for the facilities includes:

- Establishment costs;

- Running or operational costs; and

- Demobilisation costs.

Indirect Labour and Equipment

Might include general-purpose gangs and equipment to distribute men and materials around the site; site cleaning; security personnel and others not involved directly in the construction process.

Indirect equipment might include tower cranes, scaffolding and hoists that are linked directly to the time to build the project structure and some part of the finishes.

All are priced in the contract as the cost of establishing the facilities, but also electricity, water, telephone, internet etc costs; daily, weekly or monthly running costs and ultimately dismantling and removal costs upon completion.

3. Overheads

As a general rule these include:

a. Head Office overheads;

b. Insurances;

c. Bonds, financing, etc;

d. Fees.

Head Office Overheads

Normally calculated as a percentage based on the estimated yearly cost of the head office and head office personnel and the contractor’s estimated turnover per year.

Insurances

Normally based on the cost of the contractor’s turnover in a year or period.

Bonds, financing, etc

Normally based on estimated costs, sometimes dependent upon the particular contract.

Fees

Normally based on estimated costs, sometimes dependent upon the particular contract.

4. Profit

Normally a simple percentage based on the estimated turnover or value of the contract. If, for example the contractor is aiming for a 5% profit it will include an amount equal to 5% of the finalised contract sum.

Finally, prior to submitting a tender, contractors might assess and include in their estimated costs, a “better buying discount” on subcontractors and major suppliers’ work. This is normally a guess at a discount that they think they will achieve in negotiation with the subcontractors and suppliers if they win the project, as they can now demonstrate that the contract had been awarded to them.